Commissioned Memory

1965 | Victims

Resistance

Antifascist memory politics embedded the Holocaust in a rather broad historical narrative, shifting the emphasis from the portrayal of victimhood, which was considered “pessimistic,” to resistance. The plans for the 1965 exhibition were criticized by the director of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum precisely because he considered the considerable weight of the 1919–39 period disproportionate to that of the deportations in 1944.

Nevertheless, the figures and perspectives of the victims are included in the exhibits. The prisoners of the concentration camp in Gyula Konfár’s monumental painting no longer resemble protesting workers raising their fists to the sky, as in Makrisz Agamemnon’s Hungarian monument in Mauthausen (1959–64). Yet mere victimhood was not considered satisfactory: the crossed arms of the figures therefore affirm the contemporary title, Resistance in the Camp.

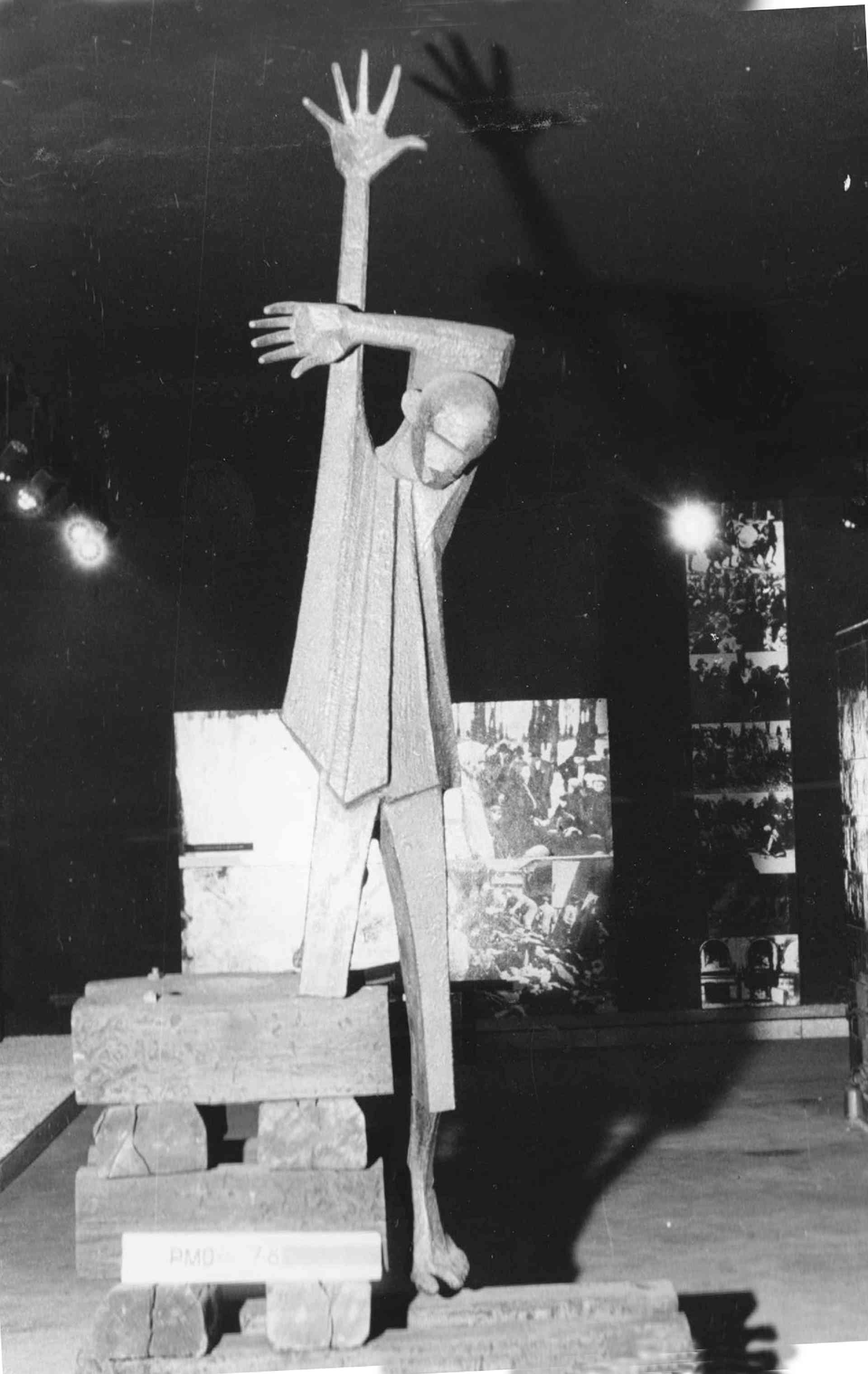

Forced March

Tibor Barabás’s sculpture entitled Forced March (1959) is a reference to the poem of the same title written by a victim of the Holocaust, Miklós Radnóti, while he was in forced labor service. The Jewish Museum, which had previously included the work in its Holocaust exhibition From Slavery to Freedom (1960), proposed the work for the exhibition in Auschwitz. The jury of the Lectorate, the commissioning body for the works, however, replied laconically that they “did not consider the work suitable.” It was certainly not primarily for aesthetic reasons, but for ideological ones: the two figures are characterized by the same “pessimism” condemned in the Mauthausen competition: they lack both resistance and martyrdom stylized as a voluntary act.

Roma Holocaust

The Roma Holocaust was completely absent from the Auschwitz exhibitions of the 1960s. To compensate for this, the earliest Hungarian artwork, the memorial design by György Jovánovics (1974), and an interview with the artist are on display on the opposite wall. József Lakatos’s short film Forgotten Dead (1981), the earliest artistic interpretation by a Roma artist, will be shown as an accompanying program to the exhibition. The first work of art by a Roma artist that partly depicts the Holocaust, Tamás Péli’s monumental painting Birth (1983), was shown to the public in 2021 at the OFF-Biennale in the Budapest History Museum.

interviewer: Daniel Véri

cameraman: Péter Szalay

editing and subtitling: Darius Krolikowski

photo (portrait): Balázs Deim

photo (works): Miklós Sulyok

Budapest, 2019